Celts versus Romans: Queen Boudicca and the Battle of Watling Street

- Gabriel Shaw

- Mar 14

- 14 min read

Updated: Mar 15

A great host charges into the clearing—churning lush grass to fresh mud. A cacophony of clanking shields and human voices rises to a deafening crescendo.

Tall, dark trees watch on as a wall of stolid crimson shields brace for the clash of mortal combat. The smell of sweat and the buzz of tension linger in the air.

For many, this will be their final day.

The Battle of Watling Street: vicious, bloody, and infused with the hatred of a people subjugated to tyrannical hegemony.

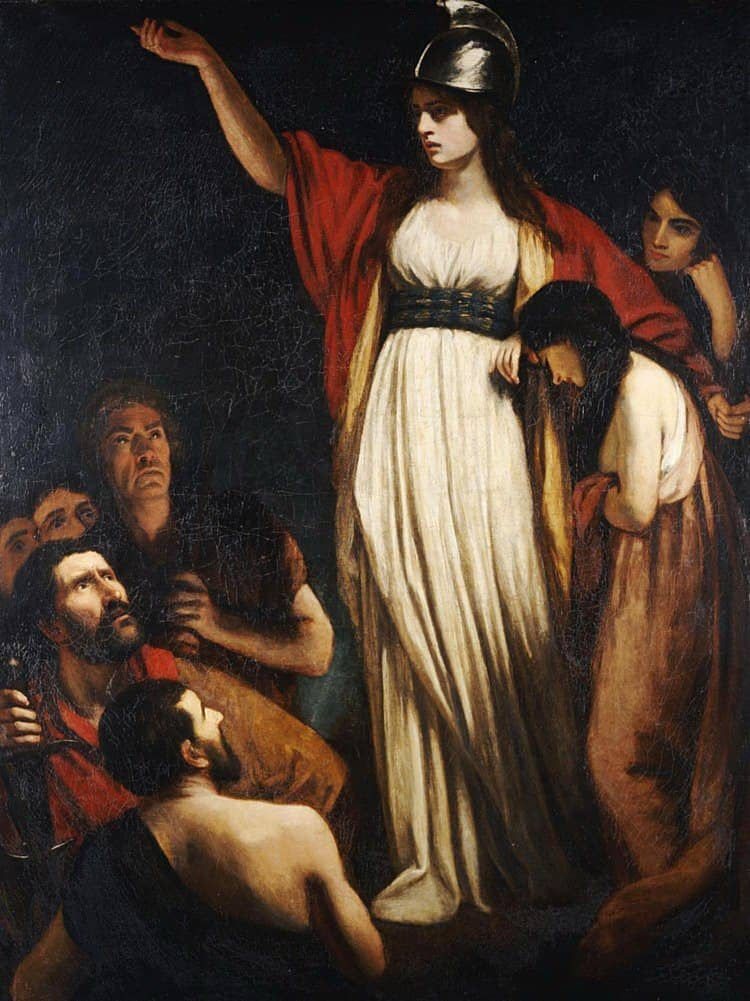

The Battle of Watling Street was a clash of two wildly opposing forces and cultures: a coalition of Celtic Britons spearheaded by the incredibly famous Boudicca of the Iceni tribe, facing off against the might of the continually expanding Roman Empire.

Causes and Context

The battle took place in either AD 60 or 61,[1] possibly in West Midlands, England.[2] Before we explore the details of this famous engagement, it’s profitable to examine the causes and nature surrounding it.

Back in 55 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar himself attempted to invade Britain, though not without numerous difficulties and setbacks, including storms en route and unfavourable engagements with the local Celts upon his arrival. At the time, the fertile island was shrouded in mystery—and some Romans doubted its existence even after Caesar's expedition.[3]

As was his nature, however, Julius Caesar was not put-off by his initial attempt, and he invaded a second time in 54 BC.

At the culmination of the second invasion, Julius Caesar left Britain altogether, though not without a strategic victory. The sheer size and appearance of the Roman army caused several of the southern Celtic tribes to ally themselves to the Romans.

It is important to consider the state of affairs among the Celts before potentially labelling such a decision as "weak". The tribes that occupied Britain rarely appear to have found themselves in union, but rather evidence would indicate that they frequently found themselves in a hostile and antagonistic relationship with each other.[4]

Thus, the decision for several tribes to ally themselves to Rome may very well have appeared a wise and profitable one.

It was almost one hundred years after this—following the installation of Emperor Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus—that the actual conquest of Britain began.

Emperor Claudius Invades Britain

In AD 43, new Emperor Claudius likely sought a way of proving himself to the relatively newly established Empire. Heralding from no military background with zero combat experience, a successful militaristic enterprise initiated under his authority would be a highly beneficial way of cementing his rule and gaining popularity.

The conquest of Britain was an ideal method for achieving this.

It wasn’t long before an unmissable opportunity presented itself. Verica, an ally of Rome, and the King of the Atrebates tribe (located in southern Britain), found himself exiled from his homeland after anti-Roman Celts began attacking his territory.

Verica fled to the Romans in need, and Rome was more than willing to oblige. Rome’s invasion could made in the name of seeking to restore Verica to his rightful throne.[5]

Claudius made preparations and appointed Aulus Plautius, a notable Roman senator who is believed to have had military experience earlier in his life, to lead the campaign.

Whatever the case, Aulus proved himself more than capable of handling the responsibility for Rome’s next greatest conquest.

Aulus Plautius left with four legions under his command and is believed to have landed in either modern-day Kent or Atrebates territory (around Hampshire and West Sussex). Both theories are plausible.

The argument for the first is based on the remnants of archeological evidence found on the Coast of Kent indicating the presence of a Roman camp. The argument for the second is that assuming the Roman’s left from Bononia (Boulogne in France) as stated by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, they would have traveled East to West to sail to West Sussex. And Cassius Dio recounts exactly that.[6]

Additionally, even though Kent would have been geographically closer to Boulogne, it is likely the Romans wouldn’t have known the precise direction to the closest point of Britain’s coastline.

However, there is a third theory that is highly plausible—that is, that both theories could be correct, as Cassius Dio tells us the Romans sailed in three divisions rather than one, meaning they could have landed at two or even three separate locations[7] and fought in multiple different battle groups as suggested by historian and archeologist, Malcom Todd.

The Battle of Medway

Even though the initial crossing of the channel and securing of the coast was not contested, it wasn’t long before the Romans encountered staunch opposition. This opposition came in the form of two powerful and influential Celtic brothers—the same brothers who had initiated the attack on Verica and imposed his exile. Now after the landing, only one side saw a decisive engagement as profitable: namely, the Romans.

The expeditionary force would likely have wanted to quench the opposition as soon as possible before the news of resistance spread to other eager ears.

The Celts; however, wanted to wear the Romans down in a clever war of attrition, forfeiting the Romans of supplies and natural resources. But in 43 AD, the Romans found the location of the main Celtic army and either drew or forced them into a pitched battle.

The two armies met at the Battle of Medway, likely near the River Medway in modern-day Kent.[8] We have very little definite information on the Battle of Medway, and so without taking the liberty of making numerous assumptions, I will stick solely to Cassius Dio's account.

What is interesting, however, is that the Roman forces present at this battle were primarily commanded by Flavius Vespasian and Titus Flavius Sabinus—two Roman brothers and commanders, only under the overall leadership of Aulus, who was leading the campaign.This could again indicate that the Roman occupying force was operating in several different groups, not just one.

Cassius tells us that the battle began when a portion of Batavian (German) auxiliary troops swam the river and met a contingent of Celtic chariots (presumably engaging them before the chariots could charge). The Roman legionaries then followed, forging the river and meeting their counterparts in vicious combat (although the River Medway could hardly be considered shallow enough for such an action today, it’s very likely the river was significantly different some two thousand years ago).[9]

This move surprised the Britons considerably, but they managed to keep their ground throughout the entire day.[10] It is that likely both sides took heavy losses during such a prolonged battle. The next day the Romans attacked and managed to drive the Britons back to the Thames.

The outcome of the battle was decisive enough for the Romans to claim possession of a large portion of the South of Britain. Caratacus, one of the brothers continued to lead resistance forces further north in a warfare comprising of skirmishes, but was either unable or unwilling to meet the Romans head-on.

The fate of the other brother is unknown, but it is very possible he was killed at Medway. Aulus Plautius, successful in the campaign, returned to Rome a hero.

Guerilla Warfare and Roman Occupation

For seven years Caratacus lead a guerrilla-style warfare, while the Romans consolidated their power within the region—establishing bases for their legionaries and subduing any rebellion from the various tribes.

Overall, the situation was looking very favourable for the Empire. It looked even more so when in AD 50 Caratacus offered the Romans a pitched battle and was dealt the coup de grâce at the Battle of Caer Caradoc. With the last flame of major resistance snuffed out, it looked as if the Romans had secured Briton at last.

Now on the 13th of October AD 54, Emperor Claudius suddenly died under suspicious circumstances. Claudius was likely killed by his wife, Agrippina the Younger,[11] who had slowly been gaining more power for herself and her son, Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (more commonly known as Nero). And so, Nero ascended to the throne.

However; the new Emperor Nero was not inclined to halt the campaigning in Britain, but on the other hand was keen to see its furtherance.

Advances into northern territories began in the same year, with the Romans expanding into Anatolia. The aim of this conquest could be considered unclear, as the land of Anatolia did not harvest the same resources as that of the more southern territories.

And this where the lack of separation between Rome’s military and political/royal figures had the ripe potential to cause issues. Acting on the commands of an emperor who sometimes only had limited military experience could lead to unfavourable situations, often then left to be dealt with by the legions direct commanders.

Nevertheless, this system had its upsides, such as the emperor often being viewed as a soldier himself—appearing more relatable to his legions. Additionally, this system meant that many of Rome’s politicians could be soldiers, and therefore offer sound military advice in a platform where they would be heard.

However you may look at it, the conquests of the north were successful.

The Iceni and Queen Boudicca

Now for a moment we’ll shift our gaze away from these territorial Roman expanses, and focus instead on an unsuspecting tribe located in the East of Britain. This tribe was the Iceni, located in modern-day Norfolk.

The Iceni was an older tribe existing from the Iron Age, and through archeological finds, appears to have been notably rich and prosperous.

Many of our excavational finds would also suggest the Iceni had an interest in horsemanship and metal work. How these things influenced the culture of the Iceni, we can’t be sure, but they were obviously of significance to them.

Since the Romans invaded Britain, the Iceni had allied themselves to their occupiers, and even agreed to pay tribute (another factor eluding to their wealth).

But all that was about to change.

In AD 60 the King of the Iceni (allowed to continue ruling under Roman supervision, and husband to a Queen named Boudicca), died. In his will, the Iceni King Prasutasgus, played a smart move, making Emperor Nero a joint heir with both his daughters.

Seeing the current situation in Britain, this would have appeared a profitable way to preserve the Iceni tribe and maintain a small degree of independence.[12]

However this was not to be.

In the same year, Roman soldiers marched on the territory, and according to Rome’s own sources, began plundering and looting and burning.

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, a Roman historian and politician who was actually alive at the time of these events recounted that Boudicca was scourged and her daughters outraged (most likely raped).[13] Who authorised these brutal actions is unclear, but they were at least permitted by Catus Decianus, the Procurator of Roman-occupied Britain at the time.

As a consequence of these actions, the Iceni tribe was essentially annexed and brought under the direct control of the Empire. However; the Romans were completely unaware of the avalanche affect that these actions were about to cause.

In roughly the same year, Queen Boudicca made her stand against the Roman Empire.

Weapons, Equipment, Style and Structure

At this point, it is profitable for us to examine the weapons, equipment, style, and structure of these two opposing forces.

By AD 60 the Romans had evolved into the highly advanced Marian Legion. Broad rectangular shields called the scutum and large, deadly-accurate javelins called the pilla were standard equipment for each well-trained legionary.

The combat style these troops thrived in was that of an infantry grind—where they would excel at wearing down and eliminating their opponents through sheer discipline and rigidity that most other forces could not compete with.

But the greatest advantage of the Marian Legion was its tactical and strategical flexibility. Their ability for every soldier to know how to erect fortifications, build bridges and other complex structures was unparalleled. Every soldier could carry a hefty pack, and march incredible distances in short time. Every legion generally had supporting cavalry and auxiliary troops. And the command structure ensured discipline and order was maintained despite the circumstances.

The Iceni people would have known a very different way of warfare compared to their Roman counterparts.

Having never faced an opposition like Rome, the Iceni would have had to realise that whatever method they relied upon for victory would have to be uniquely tailored—not the same methods which they had relied on to preserve their kingdom against other native Tribes.

The Iceni warriors would have been relatively lightly armed and armoured, carrying a mix of different shaped shields—plus a variety of swords and spears. Their armour would have comprised of a helmet—sometimes not even that—and little more.

It is in fact likely that their equipment would have been of even lesser quality than that used prior to the invasion, as it is believed the Romans had confiscated large quantities of weaponry.

However; one could say the secret weapon of the Iceni was their employment of chariots.

Unlike most chariots, the chariots used by the Iceni were generally not used for the purpose of a head-on charge, but rather to engage in quick hit-and-run skirmishes, letting loose a hail of javelins to weaken their foe.

The Iceni Strike Back

Now in a most welcome and convenient set of circumstances for the rebelling Celts, the majority of Roman forces were located in the North of Britain—engaged in the siege of the modern day Isle of Anglesey at the time of the revolt.

Because of this, Boudicca was able to assemble her army, ally with the Trinovantes tribe, and find herself almost completely unhindered to attack Roman territory. Their first target was Camulodunum, a Roman Colonia.

Camulodunum would have appeared a tempting target for several reasons.

Firstly, is was the former capital of the Trinonvantes tribe. Secondly, it housed veteran legionaries believed by the Celts to have committed atrocities against their people. Thirdly, the city held a temple dedicated to Emperor Claudius, who would have been unanimously detested by the Celts. And fourthly, and perhaps the most advantageous of all, the Colonia had no outer walls, meaning a prolonged siege would not be necessary.

Receiving word of the impending arrival of such a force, and with their own garrison having marched North, Camulodunum sent word for aide to Catus Decianus, the Roman Procurator of Britain.[14] However, there was obviously either an apparent lack of communication between Camulodunum and Catus Decianus, or just a severe lack of understanding on the part of the Procurator, for all he decided to send was a meagre 200 slaves[15] armed for combat.

They arrived at the Colonia before Boudicca and her united army. Yet sensing something that Decianus could not, 2000 legionaries from the Ninth Legio Hispana force-marched to Camulodunum, arriving shortly after Boudicca.

Unfortunately, whether as a result of a lack of scouting or because of their desperation to save their comrades, the legionaries marched straight into a trap.

With very few surviving sources regarding this engagement, it’s nonetheless clear the Celts attacked and killed almost every member of Ninth Legion present—with only a small quantity of cavalry managing to escape.[16]

With the relief force disposed of, the Celts swarmed Camulodunum, and in a complete blood-lust, massacred its inhabitants by fire, gibbet and cross.[17] Archeological evidence suggests the entire place was raised to the ground, and utterly destroyed, dissected stone by stone.

For the Celts, it would have been a serious morale and confidence booster.

Hit with this horrifying news, Catus Decianus fled Britain to Gaul.

Queen Boudica's Victory Continues

Still fresh after this victory, the Iceni and Trinovantes marched toward the city of Londinium.

Meanwhile, word of the loss of Camulodunum swiftly reached General Paulinus while he was still serving in the Northern theatre. (This is the same Paulinus who had arrived with the initial invasion roughly seventeen years before.)

Realising what the Procurator did not, Paulinus quickly led a large mounted contingent South, ordering his legions to follow in short order.

Travelling at startling speed, Paulinus arrived at Londinium before the Celts. However upon arrival, even Paulinus was evidently shocked at the sheer size of Boudicca’s army, and thus made the difficult decision not to engage, but instead to wait for his legionaries arrive.

This of course preserved Paulinus’ cavalry and tactical flexibility for a future battle, but left Londinium to a devastating fate.

The city’s inhabitants were completely massacred, and the city demolished. According to Cassius Dio, the Celts also made sacrifices and impaled the City’s most noble woman. Paulinus could do nothing but watch as the Celts moved toward their next target: Verulamium.

Whether the population of Verulamium was warned in time or not before Boudicca’s arrival remains unclear. Some sources say the lack of Roman coins at the archeological sight could indicate the people were able to flee with their possessions.[18] Whatever the case, citizens present or not, the city was raised to the ground.

It is estimated that between 70,000 and 80,000 civilians (both Roman and Roman allied Britons) were massacred in these consecutive attacks.

Finally united with his army, Paulinus now attempted to draw Boudicca and her forces out to meet him in pitched battle.

The Celts were only too eager to meet their bitter foe.

The Deciding Engagement

Boudicca and her army marched straight towards Paulinus’ position where he had carefully and meticulously chosen the ideal battlefield for his numerically inferior army.

If Boudicca had decided not to agree to the engagement, the Romans could only have watched on as the Britons moved from city to city, but the Celts obviously wanted to clinch the war.

The battleground Paulinus had chosen was a narrow defile with thick forest to its rear.[19] This allowed only one direction of attack: from the front.

The legionaries formed up in a compact formation—with auxiliaries and cavalry on the flanks.

The Roman army totalled around 10,000 men.

The legions waited, facing a force with numbers supposedly anywhere from 100,000 to 230,000. However, since the historian Tacitus was alive at the time of these events, we shall, for consistency’s sake, use his estimate of 100,000 instead of Cassius Dio’s claim of over twice that figure. It is in fact possible that even Tacitus’ number is an exaggeration, but we have little evidence to justifiably question it.

Whatever the size, it has been theorised that Paulinus did not even consider victory a possibility, and that his position was merely a way of replicating that of King Leonardis leading his remaining 300 Spartans in a final show of bravery and glory.

It was not long before the Britons arrived and prepared to attack—forming up their wagons in a half-moon shape, subsequently cutting off their own retreat. The families of the Celtic warriors watched on, hoping to spectate a massacre.

Queen Boudicca, the Iceni, and the Battle of Watling Street

The battle began with the Celts advancing into the defile.

At this point, some sources tell us the Iceni chariots moved further forward to unleash their javelins, before pulling back. Whatever the case, funnelled by the restrictive terrain, the Celts had to draw closer and closer to together as they moved forward.

When the Britons were not far out from the steady line of Roman infantry, the legionaries released their pillum at deadly close range.

The affect was crippling.

Lightly armoured, the javelins ripped through the entire front lines of the Iceni and Trinovantes. The Celts wavered. The way the pillum was designed also meant that is was impossible for the Celts to remove the javelins from their shields, and so many of the infantry would have been forced to fight without their main or only source of protection.

It was at this time that the Roman legionaries made a slow advance to meet the Celts in a wedge-like formation.[20] It is possible this consisted of multiple small wedges designed to cut through the Celtic lines at several points and ensue chaos. The lines clashed and it was soon apparent that the Britons were no match for the Marian Legion.

Crippled by the javelins, and quickly losing morale, the Celts—despite their massive numerical advantage—were systematically massacred where they stood.

Now, cut off by their own wagons, the Icneni and Trinovantes had no means of escape.

The Romans didn’t hesitate for a moment and continued to advance, killing every tribesman who stood in their way.

Eventually turning to the families of the warriors, the Romans spared none, killing women and children at will.

The Battle of Watling Street was over, and it was a completely one-sided massacre. Queen Boudicca fled the scene atop her chariot, and is later believed to have committed suicide in the aftermath of the catastrophe, or died of sickness.

Whatever the case, her death marked the end of the rebellion.

The Britons are believed to have lost upwards of 80,000, while Roman losses were around 400.[21]

The battle marked the end of the revolt, and a re-stabilisation of Roman power within Britain. The Roman presence would remain on the Island for around another 350 years. But arguably nothing would test and challenge the Roman occupation quite so much as the Boudiccan Revolt.

Endnotes:

Neither Dio or Tacitus say explicitly in which year the battle took place.

Most historians suggest a location in West Midlands, not too far from Birmingham; however others have suggested a location nearer London, or even Warwickshire.

Plutarch, The Life of Caesar, 23.3

Although there is little to no documentation recording internal conflicts among the Celts, the hundreds of hill forts and defensive fortifications found in Britain would definitely indicate to rivalry and conflict between tribes.

Cassius Dio. Roman History 60:19, pg. 415.

Cassius Dio. Roman History 60:19, pg. 417.

Cassius Dio. Roman History 60:19 pg. 417.

The supposed location of this battle could serve as a piece of evidence alluding to the Roman army landing in Kent, but if this is the case, it certainly doesn’t rule out a landing in West Sussex, because depending on the location of the Celtic forces, it’s very possible the Romans marched the distance. In fact the distance from West Sussex to Kent by foot is only twenty hours.

https://www.roman-britain.co.uk/roman-conquest-and-occupation-of-britain/initial-claudian-invasion-and conquest-43-60-ad/the-battle-of-medway/

Cassius Dio. Roman History 60:19 pg. 419

Cassius Dio. Roman History 61:34 pg. 29-31

Tacitus. The Annals. 14:31

Tacitus. The Annals. 14:31

Tacitus. The Annals. 14:32

It is possible this small relief force was comprised of Roman Auxiliaries; however Tacitus tells us they were ‘without regular arms.’ (Tacitus. The Annals 14:32).

Tacitus. The Annals 14:32

Tacitus. The Annals 14:33

Tacitus. The Annals 14:34

Tacitus. The Annals 14:37

Tacitus. The Annals 14:37

Primary Sources:

Tacitus. The Annals and The Histories. Translated by AJ Church and WJ Brodribb. Washington Square Press, New York: 1964.

Cassius Dio. Dio’s Roman History with an english translation by Earnest Cary Ph.D. On the basis of the version by Herbert Baldwin Foster. William Heinemann LTD. Harvard university Press: 1955.

Online Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Caesar's_invasions_of_Britain https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boudican_revolt#Verulamium https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_conquest_of_Britain

https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Watling-Street https://www.britishbattles.com/wars-of-roman-britain/battle-of-medway/ https://www.imagininghistory.co.uk/post/britain-before-the-romans https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/story-of-england/romans/invasion

What a great article, Gabriel! Watling Street is an iconic battle story, and you have retold it in an incredibly accessible format—balancing narrative with historical rigour (including engaging with primary source sources) really fabulously.

It was a joy to read!